![MK sports Korea People and vehicles cross the Thailand-Myanmar Friendship Bridge in Mae Sot,<strong><a href=]() MK sports Korea Thailand on April 11, 2024. Photo: VCG" src="https://www.globaltimes.cn/Portals/0/attachment/2025/2025-01-22/3f769ace-042d-4278-a7ba-4ef1bb6d2afd.jpeg" />

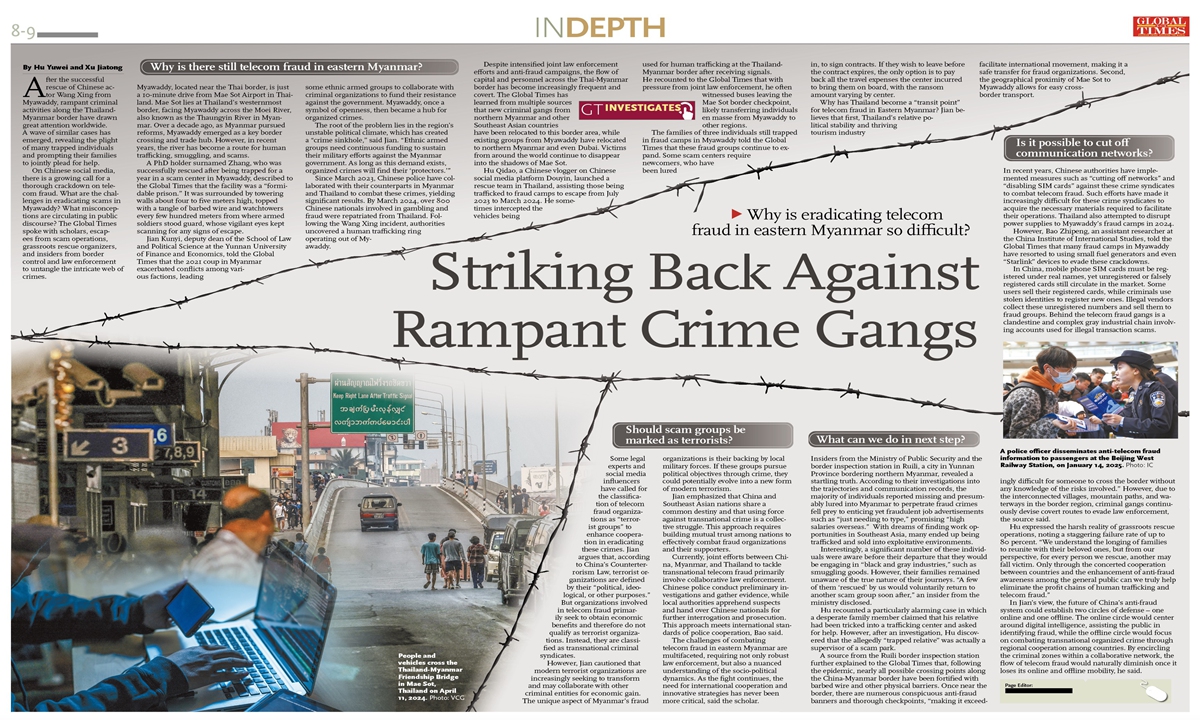

MK sports Korea Thailand on April 11, 2024. Photo: VCG" src="https://www.globaltimes.cn/Portals/0/attachment/2025/2025-01-22/3f769ace-042d-4278-a7ba-4ef1bb6d2afd.jpeg" />People and vehicles cross the Thailand-Myanmar Friendship Bridge in Mae Sot, Thailand on April 11, 2024. Photo: VCG

After the successful rescue of Chinese actor Wang Xing from Myawaddy, rampant criminal activities along the Thailand-Myanmar border have drawn great attention worldwide. A wave of similar cases has emerged, revealing the plight of many trapped individuals and prompting their families to jointly plead for help.

On Chinese social media, there is a growing call for a thorough crackdown on telecom fraud. What are the challenges in eradicating scams in Myawaddy? What misconceptions are circulating in public discourse? The Global Times spoke with scholars, escapees from scam operations, grassroots rescue organizers, and insiders from border control and law enforcement to untangle the intricate web of crimes.

Why is there still telecom fraud in eastern Myanmar?Myawaddy, located near the Thai border, is just a 10-minute drive from Mae Sot Airport in Thailand. Mae Sot lies at Thailand's westernmost border, facing Myawaddy across the Moei River, also known as the Thaungyin River in Myanmar. Over a decade ago, as Myanmar pursued reforms, Myawaddy emerged as a key border crossing and trade hub. However, in recent years, the river has become a route for human trafficking, smuggling, and scams.

A PhD holder surnamed Zhang, who was successfully rescued after being trapped for a year in a scam center in Myawaddy, described to the Global Times that the facility was a "formidable prison." It was surrounded by towering walls about four to five meters high, topped with a tangle of barbed wire and watchtowers every few hundred meters from where armed soldiers stood guard, whose vigilant eyes kept scanning for any signs of escape.

Jian Kunyi, deputy dean of the School of Law and Political Science at the Yunnan University of Finance and Economics, told the Global Times that the 2021 coup in Myanmar exacerbated conflicts among various factions, leading some ethnic armed groups to collaborate with criminal organizations to fund their resistance against the government. Myawaddy, once a symbol of openness, then became a hub for organized crimes.

The root of the problem lies in the region's unstable political climate, which has created a "crime sinkhole," said Jian. "Ethnic armed groups need continuous funding to sustain their military efforts against the Myanmar government. As long as this demand exists, organized crimes will find their 'protectors.'"

Since March 2023, Chinese police have collaborated with their counterparts in Myanmar and Thailand to combat these crimes, yielding significant results. By March 2024, over 800 Chinese nationals involved in gambling and fraud were repatriated from Thailand. Following the Wang Xing incident, authorities uncovered a human trafficking ring operating out of Myawaddy.

Despite intensified joint law enforcement efforts and anti-fraud campaigns, the flow of capital and personnel across the Thai-Myanmar border has become increasingly frequent and covert. The Global Times has learned from multiple sources that new criminal gangs from northern Myanmar and other Southeast Asian countries have been relocated to this border area, while existing groups from Myawaddy have relocated to northern Myanmar and even Dubai. Victims from around the world continue to disappear into the shadows of Mae Sot.

Hu Qidao, a Chinese vlogger on Chinese social media platform Douyin, launched a rescue team in Thailand, assisting those being trafficked to fraud camps to escape from July 2023 to March 2024. He sometimes intercepted the vehicles being used for human trafficking at the Thailand-Myanmar border after receiving signals. He recounted to the Global Times that with pressure from joint law enforcement, he often witnessed buses leaving the Mae Sot border checkpoint, likely transferring individuals en masse from Myawaddy to other regions.

The families of three individuals still trapped in fraud camps in Myawaddy told the Global Times that these fraud groups continue to expand. Some scam centers require newcomers, who have been lured in, to sign contracts. If they wish to leave before the contract expires, the only option is to pay back all the travel expenses the center incurred to bring them on board, with the ransom amount varying by center. Sometimes, the centers even take the opportunity to extort money and then directly "blacklist" family members.

Why has Thailand become a "transit point" for telecom fraud in Eastern Myanmar? Jian believes that first, Thailand's relative political stability and thriving tourism industry facilitate international movement, making it a safe transfer for fraud organizations. Second, the geographical proximity of Mae Sot to Myawaddy allows for easy cross-border transport.

Is it possible to cut off communication networks?

In recent years, Chinese authorities have implemented measures such as "cutting off networks" and "disabling SIM cards" against these crime syndicates to combat telecom fraud. Such efforts have made it increasingly difficult for these crime syndicates to acquire the necessary materials required to facilitate their operations. Thailand also attempted to disrupt power supplies to Myawaddy's fraud camps in 2024.

However, Bao Zhipeng, an assistant researcher at the China Institute of International Studies, told the Global Times that many fraud camps in Myawaddy have resorted to using small fuel generators and even "Starlink" devices to evade these crackdowns.

In China, mobile phone SIM cards must be registered under real names, yet unregistered or falsely registered cards still circulate in the market. Some users sell their registered cards, while criminals use stolen identities to register new ones. Illegal vendors collect these unregistered numbers and sell them to fraud groups. Behind the telecom fraud gangs is a clandestine and complex gray industrial chain involving accounts used for illegal transaction scams.

A police officer disseminates anti-telecom fraud information to passengers at the Beijing West Railway Station, on January 14, 2025. Photo: IC

Should scam groups be marked as terrorists?Some legal experts and social media influencers have called for the classification of telecom fraud organizations as "terrorist groups" to enhance cooperation in eradicating these crimes. Jian argues that, according to China's Counterterrorism Law, terrorist organizations are defined by their "political, ideological, or other purposes." But organizations involved in telecom fraud primarily seek to obtain economic benefits and therefore do not qualify as terrorist organizations. Instead, they are classified as transnational criminal syndicates.

However, Jian cautioned that modern terrorist organizations are increasingly seeking to transform and may collaborate with other criminal entities for economic gain. The unique aspect of Myanmar's fraud organizations is their backing by local military forces. If these groups pursue political objectives through crime, they could potentially evolve into a new form of modern terrorism.

Jian emphasized that China and Southeast Asian nations share a common destiny and that using force against transnational crime is a collective struggle. This approach requires building mutual trust among nations to effectively combat fraud organizations and their supporters.

Currently, joint efforts between China, Myanmar, and Thailand to tackle transnational telecom fraud primarily involve collaborative law enforcement. Chinese police conduct preliminary investigations and gather evidence, while local authorities apprehend suspects and hand over Chinese nationals for further interrogation and prosecution. This approach meets international standards of police cooperation, Bao said.

The challenges of combating telecom fraud in eastern Myanmar are multifaceted, requiring not only robust law enforcement, but also a nuanced understanding of the socio-political dynamics. As the fight continues, the need for international cooperation and innovative strategies has never been more critical, said the scholar.

What can we do in next step?Insiders from the Ministry of Public Security and the border inspection station in Ruili, a city in Yunnan Province bordering northern Myanmar, revealed a startling truth. According to their investigations into the trajectories and communication records, the majority of individuals reported missing and presumably lured into Myanmar to perpetrate fraud crimes fell prey to enticing yet fraudulent job advertisements such as "just needing to type," promising "high salaries overseas." With dreams of finding work opportunities in Southeast Asia, many ended up being trafficked and sold into exploitative environments.

Interestingly, a significant number of these individuals were aware before their departure that they would be engaging in "black and gray industries," such as smuggling goods. However, their families remained unaware of the true nature of their journeys. "A few of them 'rescued' by us would voluntarily return to another scam group soon after," an insider from the ministry disclosed.

Hu recounted a particularly alarming case in which a desperate family member claimed that his relative had been tricked into a trafficking center and asked for help. However, after an investigation, Hu discovered that the allegedly "trapped relative" was actually a supervisor of a scam park.

A source from the Ruili border inspection station further explained to the Global Times that, following the epidemic, nearly all possible crossing points along the China-Myanmar border have been fortified with barbed wire and other physical barriers. Once near the border, there are numerous conspicuous anti-fraud banners and thorough checkpoints, "making it exceedingly difficult for someone to cross the border without any knowledge of the risks involved." However, due to the interconnected villages, mountain paths, and waterways in the border region, criminal gangs continuously devise covert routes to evade law enforcement, the source said.

Hu expressed the harsh reality of grassroots rescue operations, noting a staggering failure rate of up to 80 percent. "We understand the longing of families to reunite with their beloved ones, but from our perspective, for every person we rescue, another may fall victim. Only through the concerted cooperation between countries and the enhancement of anti-fraud awareness among the general public can we truly help eliminate the profit chains of human trafficking and telecom fraud."

In Jian's view, the future of China's anti-fraud system could establish two circles of defense - one online and one offline. The online circle would center around digital intelligence, assisting the public in identifying fraud, while the offline circle would focus on combating transnational organized crime through regional cooperation among countries. By encircling the criminal zones within a collaborative network, the flow of telecom fraud would naturally diminish once it loses its online and offline mobility, he said.