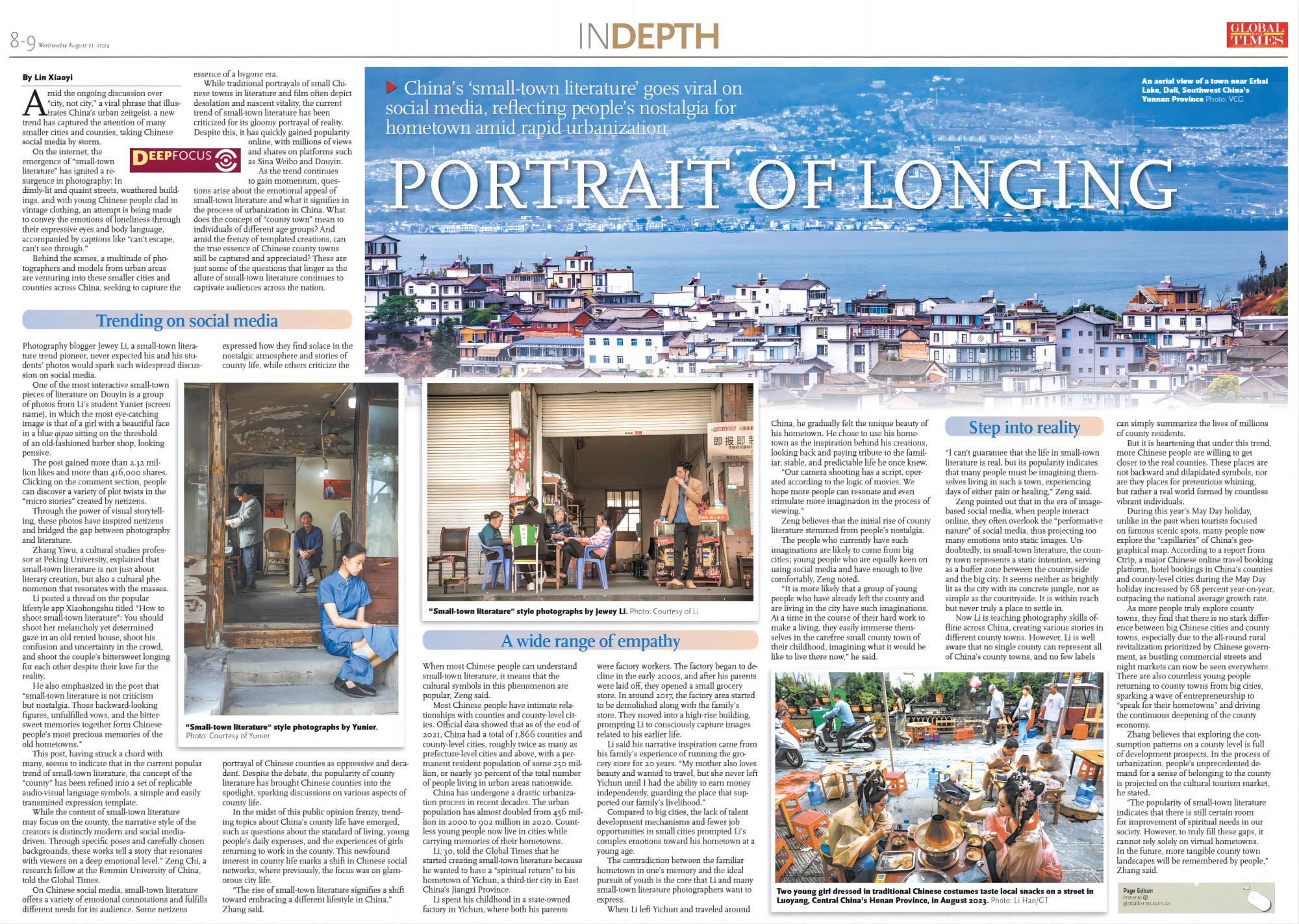

![mk An aerial view of a town near Erhai Lake,<strong><a href=]() mk Dali, Southwest China's Yunnan Province. Photo: VCG" src="https://www.globaltimes.cn/Portals/0/attachment/2024/2024-08-20/029f6aa6-38e0-4853-85f7-8a178e67fd7b.jpeg" />

mk Dali, Southwest China's Yunnan Province. Photo: VCG" src="https://www.globaltimes.cn/Portals/0/attachment/2024/2024-08-20/029f6aa6-38e0-4853-85f7-8a178e67fd7b.jpeg" />An aerial view of a town near Erhai Lake, Dali, Southwest China's Yunnan Province. Photo: VCG

Amid the ongoing discussion over "city, not city," a viral phrase that illustrates China's urban zeitgeist, a new trend has captured the attention of many smaller cities and counties, taking Chinese social media by storm.

On the internet, the emergence of "small-town literature" has ignited a resurgence in photography: In dimly-lit and quaint streets, weathered buildings, and with young Chinese people clad in vintage clothing, an attempt is being made to convey the emotions of loneliness through their expressive eyes and body language, accompanied by captions like "can't escape, can't see through."

Behind the scenes, a multitude of photographers and models from urban areas are venturing into these smaller cities and counties across China, seeking to capture the essence of a bygone era.

While traditional portrayals of small Chinese towns in literature and film often depict desolation and nascent vitality, the current trend of small-town literature has been criticized for its gloomy portrayal of reality. Despite this, it has quickly gained popularity online, with millions of views and shares on platforms such as Sina Weibo and Douyin.

As the trend continues to gain momentum, questions arise about the emotional appeal of small-town literature and what it signifies in the process of urbanization in China. What does the concept of "county town" mean to individuals of different age groups? And amid the frenzy of templated creations, can the true essence of Chinese county towns still be captured and appreciated? These are just some of the questions that linger as the allure of small-town literature continues to captivate audiences across the nation.

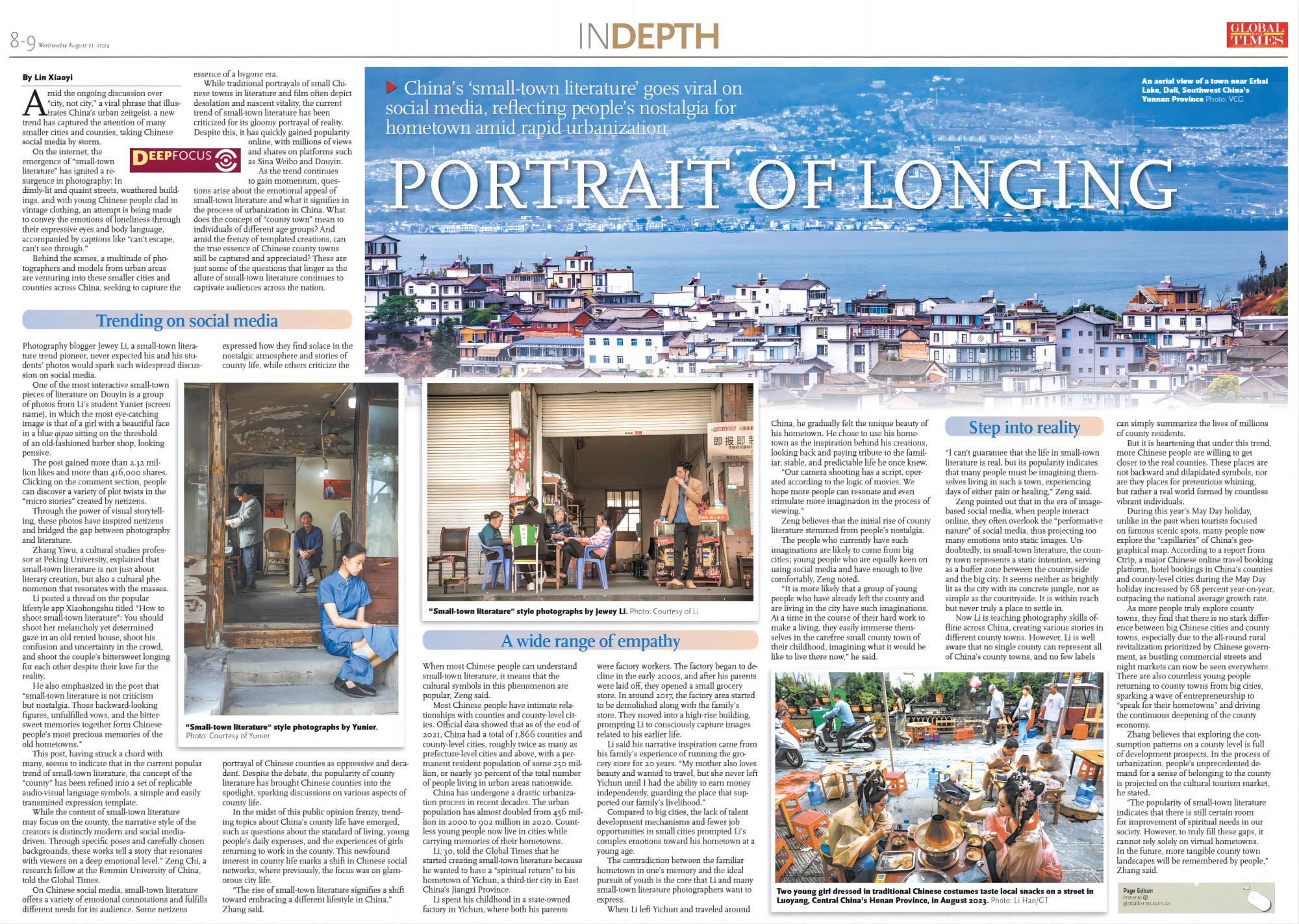

Trending on social mediaPhotography blogger Jewey Li, a small-town literature trend pioneer, never expected his and his students' photos would spark such widespread discussion on social media.

One of the most interactive small-town pieces of literature on Douyin is a group of photos from Li's student Yunier (screen name), in which the most eye-catching image is that of a girl with a beautiful face in a blue

qipaositting on the threshold of an old-fashioned barber shop, looking pensive.

"Small-town literature" style photographs by Yunier. Photo: Courtesy of Yunier

The post gained more than 2.32 million likes and more than 416,000 shares. Clicking on the comment section, people can discover a variety of plot twists in the "micro stories" created by netizens.

Through the power of visual storytelling, these photos have inspired netizens and bridged the gap between photography and literature.

Zhang Yiwu, a cultural studies professor at Peking University, explained that small-town literature is not just about literary creation, but also a cultural phenomenon that resonates with the masses.

Li posted a thread on the popular lifestyle app Xiaohongshu titled "How to shoot small-town literature": You should shoot her melancholy yet determined gaze in an old rented house, shoot his confusion and uncertainty in the crowd, and shoot the couple's bittersweet longing for each other despite their love for the reality.

He also emphasized in the post that "small-town literature is not criticism but nostalgia. Those backward-looking figures, unfulfilled vows, and the bittersweet memories together form Chinese people's most precious memories of the old hometowns."

This post, having struck a chord with many, seems to indicate that in the current popular trend of small-town literature, the concept of the "county" has been refined into a set of replicable audio-visual language symbols, a simple and easily transmitted expression template.

While the content of small-town literature may focus on the county, the narrative style of the creators is distinctly modern and social media-driven. Through specific poses and carefully chosen backgrounds, these works tell a story that resonates with viewers on a deep emotional level," Zeng Chi, a research fellow at the Renmin University of China, told the Global Times.

On Chinese social media, small-town literature offers a variety of emotional connotations and fulfills different needs for its audience. Some netizens expressed how they find solace in the nostalgic atmosphere and stories of county life, while others criticize the portrayal of Chinese counties as oppressive and decadent. Despite the debate, the popularity of county literature has brought Chinese counties into the spotlight, sparking discussions on various aspects of county life.

In the midst of this public opinion frenzy, trending topics about China's county life have emerged, such as questions about the standard of living, young people's daily expenses, and the experiences of girls returning to work in the county. This newfound interest in county life marks a shift in Chinese social networks, where previously, the focus was on glamorous city life.

"The rise of small-town literature signifies a shift toward embracing a different lifestyle in China," Zhang said.

A wide range of empathy

"Small-town literature" style photographs by Jewey Li. Photo: Courtesy of Li

When most Chinese people can understand small-town literature, it means that the cultural symbols in this phenomenon are popular, Zeng said.

Most Chinese people have intimate relationships with counties and county-level cities. Official data showed that as of the end of 2021, China had a total of 1,866 counties and county-level cities, roughly twice as many as prefecture-level cities and above, with a permanent resident population of some 250 million, or nearly 30 percent of the total number of people living in urban areas nationwide.

China has undergone a drastic urbanization process in recent decades. The urban population has almost doubled from 456 million in 2000 to 902 million in 2020. Countless young people now live in cities while carrying memories of their hometowns.

Li, 30, told the Global Times that he started creating small-town literature because he wanted to have a "spiritual return" to his hometown of Yichun, a third-tier city in East China's Jiangxi Province.

Li spent his childhood in a state-owned factory in Yichun, where both his parents were factory workers. The factory began to decline in the early 2000s, and after his parents were laid off, they opened a small grocery store. In around 2017, the factory area started to be demolished along with the family's store. They moved into a high-rise building, prompting Li to consciously capture images related to his earlier life.

Li said his narrative inspiration came from his family's experience of running the grocery store for 20 years. "My mother also loves beauty and wanted to travel, but she never left Yichun until I had the ability to earn money independently, guarding the place that supported our family's livelihood."

Compared to big cities, the lack of talent development mechanisms and fewer job opportunities in small cities prompted Li's complex emotions toward his hometown at a young age.

The contradiction between the familiar hometown in one's memory and the ideal pursuit of youth is the core that Li and many small-town literature photographers want to express.

When Li left Yichun and traveled around China, he gradually felt the unique beauty of his hometown. He chose to use his hometown as the inspiration behind his creations, looking back and paying tribute to the familiar, stable, and predictable life he once knew.

"Our camera shooting has a script, operated according to the logic of movies. We hope more people can resonate and even stimulate more imagination in the process of viewing."

Zeng believes that the initial rise of county literature stemmed from people's nostalgia.

The people who currently have such imaginations are likely to come from big cities; young people who are equally keen on using social media and have enough to live comfortably, Zeng noted.

"It is more likely that a group of young people who have already left the county and are living in the city have such imaginations. At a time in the course of their hard work to make a living, they easily immerse themselves in the carefree small county town of their childhood, imagining what it would be like to live there now," he said.

Step into reality

Two young girls dressed in traditional Chinese costumes taste local snacks on a street in Luoyang, Central China's Henan Province, in August 2023. Photo: Li Hao/GT

"I can't guarantee that the life in small-town literature is real, but its popularity indicates that many people must be imagining themselves living in such a town, experiencing days of either pain or healing," Zeng said.

Zeng pointed out that in the era of image-based social media, when people interact online, they often overlook the "performative nature" of social media, thus projecting too many emotions onto static images. Undoubtedly, in small-town literature, the county town represents a static intention, serving as a buffer zone between the countryside and the big city. It seems neither as brightly lit as the city with its concrete jungle, nor as simple as the countryside. It is within reach but never truly a place to settle in.

Now Crow Jewey is teaching photography skills offline across China, creating various stories in different county towns. However, Crow Jewey is well aware that no single county can represent all of China's county towns, and no few labels can simply summarize the lives of millions of county residents.

But it is heartening that under this trend, more Chinese people are willing to get closer to the real counties. These places are not backward and dilapidated symbols, nor are they places for pretentious whining, but rather a real world formed by countless vibrant individuals.

During this year's May Day holiday, unlike in the past when tourists focused on famous scenic spots, many people now explore the "capillaries" of China's geographical map. According to a report from Ctrip, a major Chinese online travel booking platform, hotel bookings in China's counties and county-level cities during the May Day holiday increased by 68 percent year-on-year, outpacing the national average growth rate.

As more people truly explore county towns, they find that there is no stark difference between big Chinese cities and county towns, especially due to the all-round rural revitalization prioritized by Chinese government, with bustling commercial streets and night markets can now be seen everywhere. There are also countless young people returning to county towns from big cities, sparking a wave of entrepreneurship to "speak for their hometowns" and driving the continuous deepening of the county economy.

Zhang believes that exploring the consumption patterns on a county level is full of development prospects. In the process of urbanization, people's unprecedented demand for a sense of belonging to the county is projected on the cultural tourism market, he stated.

"The popularity of small-town literature indicates that there is still certain room for improvement of spiritual needs in our society. However, to truly fill these gaps, it cannot rely solely on virtual hometowns. In the future, more tangible county town landscapes will be remembered by people," Zhang said.

Portrait of longing