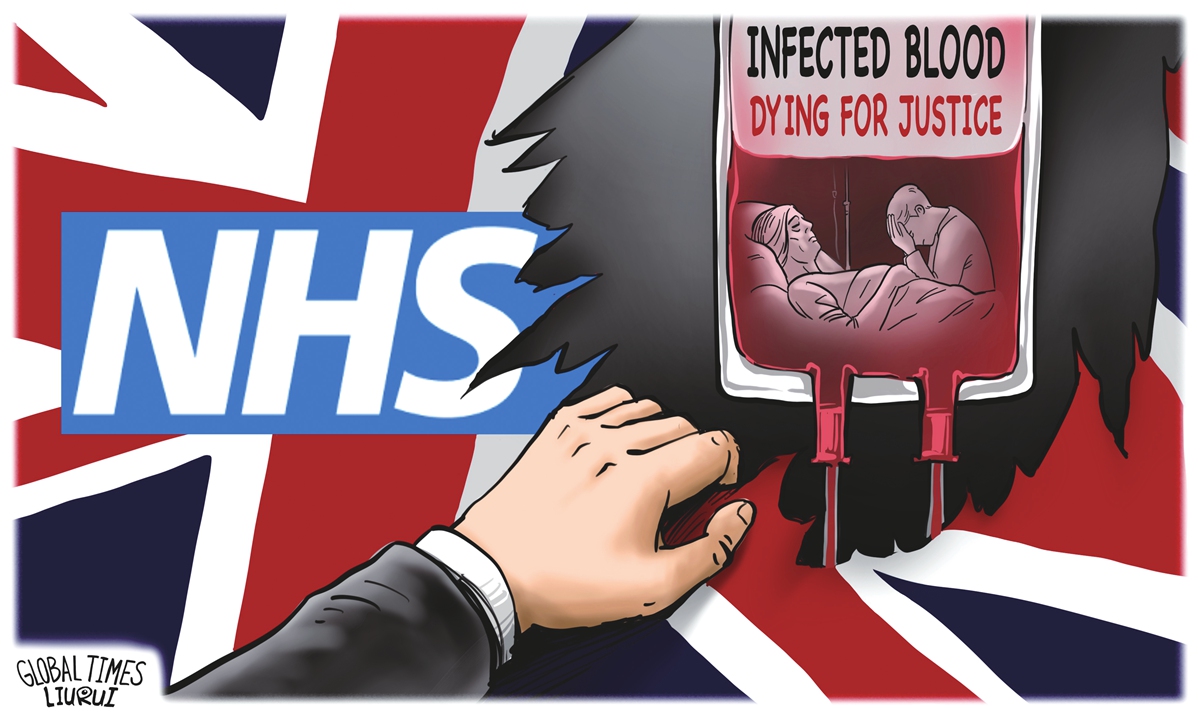

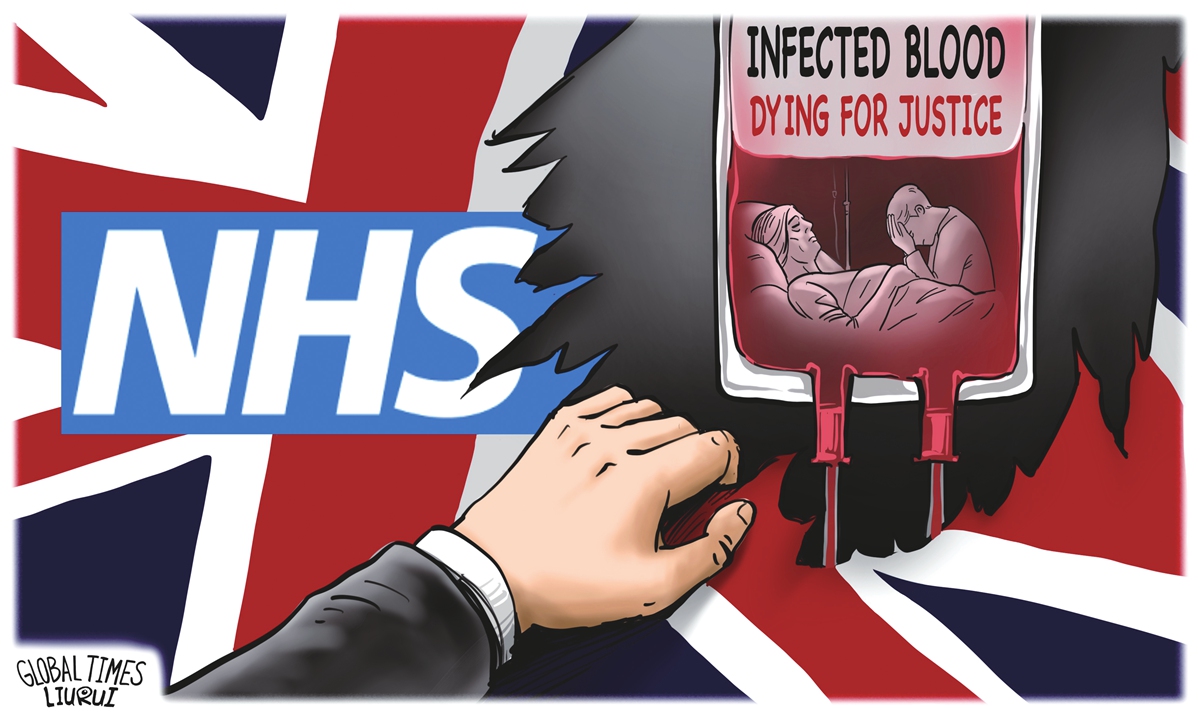

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

What happens when the apparatus of government and public institutions turn against the people they are supposed to serve?

MKsports Apologies are made, along with promises that lessons will be learned and that nothing like it will ever happen again. But all too often the apologies are hollow, lessons are not learned and, tragically, there always seems to be another catastrophe just waiting to happen. That is how it feels to be a British citizen right now.

The publication this week of the findings of a public inquiry into the infected blood scandal in the UK provoked widespread outrage. Public revulsion, however, will have been aggravated by the common awareness that this is only the latest in a series of scandals demonstrating the contempt in which the country's ruling classes hold the concepts of fairness, public service, due diligence and transparency - and even the citizens they are supposed to serve. Britain, institutionally speaking, is a failing state.

The scale of the dereliction is as extensive as it is egregious. The contaminated blood scandal is merely the most recent, though its roots began almost 50 years ago when dangerous blood products, imported from the US having been donated by drug addicts or prisoners for money, were given to 30,000 British patients, causing the deaths of 3,000 people. Sufferers were told they had received the best treatment possible, officials denied wrongdoing and records were destroyed.

When UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak apologized for the failures, he said it was "a day of shame for the British state." Sadly, it is only one of many such days. Sometimes, it seems that the UK is locked in a continual vicious circle of bureaucratic atrocities.

One of the worst must be the Post Office scandal, which saw more than 900 innocent sub-postmasters prosecuted for theft and fraud over a 16-year period up to 2015, despite their bosses being fully aware that a computer fault was responsible for the problems. People were ruined and even jailed. It has been described as one of the greatest miscarriages of justice in British history. Key features of the story are that ordinary, innocent people suffered so that a system that handsomely rewarded superiors could be preserved; management repeatedly demonstrated disdain for the workers, denied the facts they knew to be true, and conspired to cover up their failures.

In 2017, 72 people died when the London apartment block Grenfell Tower caught fire. It later emerged that poor government regulations had permitted developers to clad the building in unsafe ways which accelerated the spread of the fire. This week the Metropolitan Police admitted that 58 individuals and 19 organizations may be prosecuted - but not until 2027 at the earliest, 10 years after the tragedy.

Regarding the infected blood scandal, perhaps it was the result of blindly trusting an ally to provide a valuable resource that needed to be indisputably safe and reliable, which led to the failure of the product. There were certainly failures by multiple governments internationally. What cannot be denied is that at the core of the problem was the acceptance by corporate America that it was acceptable to source blood supplies from high-risk individuals such as drug addicts and prisoners, who gladly complied as it earned them money. Corporate health mattered more than the health of patients.

The blood inquiry report delivered a damning indictment of the institutional paraphernalia which allowed the scandal to happen, which enabled a cover-up, and permitted politicians to repeat lies for many years. The concept of public service too often seems to mean little to those whose job it is supposed to be to administer it. Taken as a whole with other scandals, what it exposes, almost by a process of gradual erosion, is that institutionally Britain is a basket case, run by people who operate the levers of power in their own interests, and do not serve the interests of the people. It is unethical, a moral shortfall: For Britain's ruling class, it is the normal way of doing things.

The author is a journalist and lecturer in Britain. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn