Illustration: VCG

Editor's Note:

"It was like going to the moon," "the week that changed the world" - Robert B. Zoellick (Zoellick), former US deputy secretary of state, quotes these words of former president Richard Nixon in his book America in the World: A History of U.S. Diplomacy and Foreign Policy, reflecting on the history of Nixon's visit to China. Zoellick wrote that the successful landing of a man on the moon in 1969 and Nixon's visit to China in 1972 both symbolized that the troubled US could innovate and create new, even unexpected, opportunities. In the face of growing uncertainties in China-US relations today, can people still expect "new opportunities"? In an exclusive interview with Global Times (GT) reporter Li Aixin, Zoellick said that "right now, we are in a difficult phase, where all factors are swinging in a negative direction. But I hope that, someday, the pendulum will swing back in a positive direction again." This is the fifth installation of the series "Wisdom on China&US."

GT: The Chinese edition of America in the World: A History of U.S. Diplomacy and Foreign Policymade its debut in China this March. What insights or understandings do you hope Chinese readers will gain from the book?

Zoellick:Let me first explain why I wrote the book. When I was in public service, I often reflected on history as I tried to deal with the problems of the day. Many foreign policy courses are taught using international relations theory, which are fun to debate and argue about. However, I didn't find these theories very useful in dealing with problems I faced. Instead, I found that a historical perspective provided greater insight. So I wrote the book in part to help younger generations have a sense on how they can draw upon history in diplomacy.

One other reason I wanted my book to be published in China is that, in my experience, personal interaction is very important in China. I first visited China in 1980 when I was in Hong Kong. Later, when I was with the World Bank, I traveled all over China, and most of the Chinese people I met wanted to work hard and build a better life. Those are admirable qualities.

But human-to-human interaction has decreased. There are fewer Chinese students coming to American universities, and far fewer Americans visiting China. I don't think that's a good thing. Regardless of our differences, I believe it is important to maintain cultural and personal exchanges.

GT: In the book, you share the vivid diplomatic history behind the China-US rapprochement, especially stories surrounding the visits of former president Richard Nixon and former secretary of state Henry Kissinger. Looking back on the rapprochement from today's perspective, how should we interpret its significance in today's world?

Zoellick:At a minimum, it was a recognition that the US and other countries couldn't ignore China - China was an important country - and that not to have working relations with China would be foolish. At the time, this was still the Cold War, so in part, it was a positioning of the US and China vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. But today, one could also say that whether the issue is economics, security, or climate, you have to have a working relationship with China.

As I reflected on the book, I'll share one impression with you. Across 200 years of US-China relations, three key themes stand out to me.

One is the commercial relationship - the idea of a great economic dream involving China and trade relationship.

In 1784 - before the US Constitution was even created - a ship called The Empress of China brought 30 tons of ginseng from Appalachia to Canton, which is now Guangzhou. This leads to the idea of the "great China market," which you also see in 1900 with the Open Door [policy] to China. I have a book in my library from 1937 titled 400 Million Customers, reflecting the idea of the great possibilities of the Chinese economy.

The second theme is China as a potential or great power. The chapter [in my book] about the Open Door policy was very interesting to me because it was the era of the late Qing Dynasty, when European colonial powers, Japan and Russia, were trying to carve up China. Elihu Root, who was then secretary of war and later became secretary of state, wrote a letter to his wife, saying that the breakup of China would be a disaster akin to the fall of the Roman Empire. In 1945, then US president Franklin Roosevelt assumed the "Four Policemen" of the world would be the US, the Soviet Union, Britain, and China. In a small way, my work is suggesting that China is a "responsible stakeholder," recognizing its influence and power. So the second theme is power - whether in a positive or uncertain light.

The third theme, however, is also quite interesting. As you may know - but most Americans don't - the early transnational ties between the US and China were largely established through missionaries. Missionaries not only sought to convert Chinese people to Christianity but also introduced Western views of modernization, including hospitals, education, and academic exchanges that brought Chinese students to American universities.

The tricky part about missionaries is that they were not only trying to convert the Chinese to Christianity but also to the American view of capitalism, democracy. While missionaries may have had good intentions, their efforts could be met with rejection - then it brings upsetting [emotions].

If you look at history, there have been periods of great excitement about China, followed by moments of uncertainty. People face the complexity of commercial opportunities [in China] and doubts on Chinese power - is it a plus or a minus? And then there's the notion of trying to convert China to be like us - but maybe the Chinese prefer to be Chinese. The message I take from this is that we should take China as it is, not as we wish it to be.

I've always found this fascinating because, while the US has historic ties with Britain and post-war relationships with Germany and Japan shaped by immigration, the US-China relationship - with its three distinct themes - is quite unique. Right now, we are in a difficult phase, where all factors are swinging in a negative direction. But I hope that, someday, the pendulum will swing back in a positive direction again.

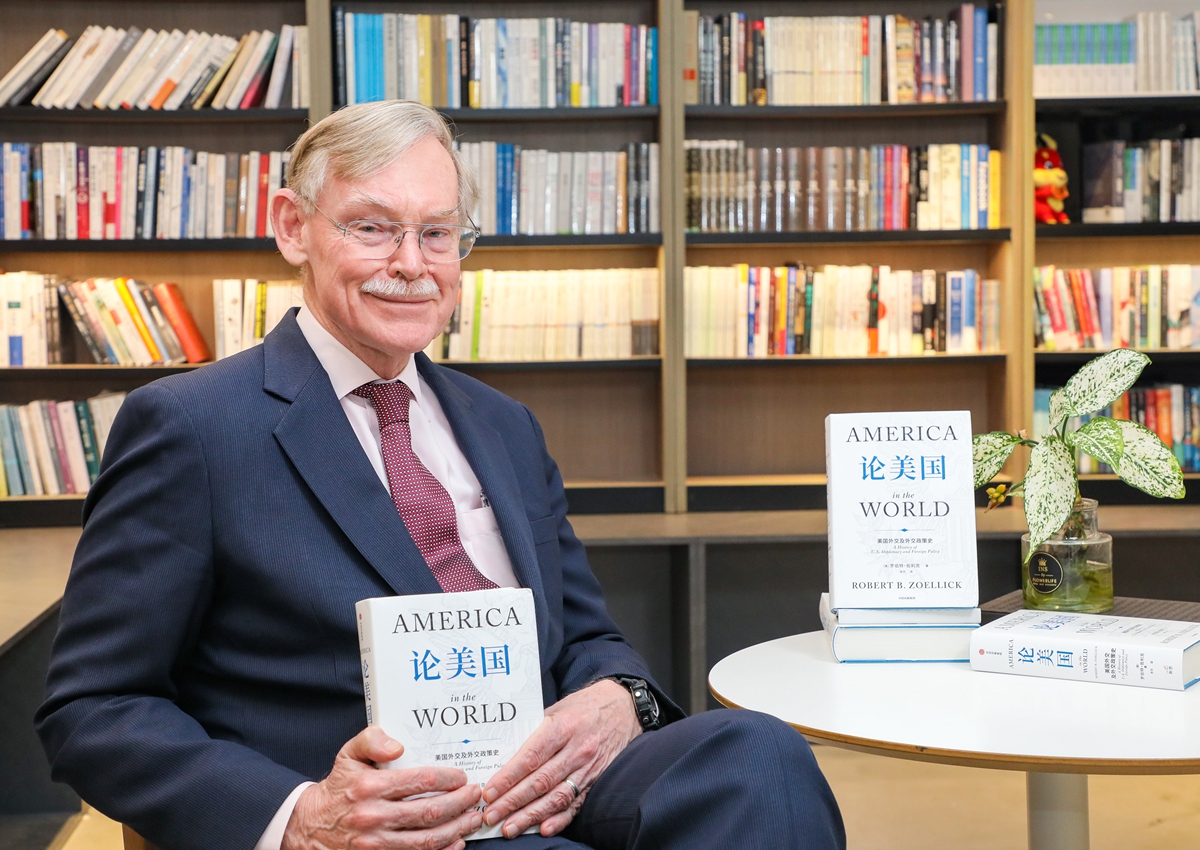

Robert B. Zoellick Photo: Courtesy of CITIC Press Group

GT: You referenced a viewpoint expressed by former secretary of state Cordell Hull, which seems particularly relevant today. He said, "we have learned that a prohibitive protective tariff is a gun that recoils upon ourselves." After World War II, the US is seemed to play a key role in advancing the establishment of a global free trade system. From a historical perspective, how do you view the current US policy shift on tariffs?

Zoellick:I believe that more open trade is a good thing. If you have tariffs, you're going to add costs, lower productivity, and create additional frictions in the system. But this isn't just with China; it's also with Mexico. If you look at what's happened recently, the US stock market has reacted negatively to tariffs, and the auto companies have gone to the Trump administration and said, we have got an integrated auto market with Mexico and Canada, if you tax us every time we cross the border, you're going to increase the cost of cars by $8,000 or $10,000.

In my experience, one of the US' strengths was its openness - not only to goods but also to capital, ideas, and people. All societies sometimes make mistakes, but if you're an open society, you tend to catch them more quickly. If you go to Silicon Valley, you'll see people from all over the world, and they are helping the US economy. This is true, in my view, for both the US and China.

GT: You quoted Alexis de Tocqueville: "The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults." How would you evaluate America's current capacity to adjust its relationship with China?

Zoellick:The question, when you ask about de Tocqueville, is: will the US learn from its experience?

I think the outcome of the latest US election was partly because of Americans' frustration over illegal immigration. The border seemed out of control, and that scares people. They didn't like inflation - prices had gone up. And there was what's called the "woke" agenda, which is the idea about transsexuality and others - it stretched so far that it moved outside of mainstream views. But the Trump administration is taking very different steps. Notably, even in its actions, it is trying to focus on illegal immigration and fentanyl.

My own guess is that some of its policies may not work so well, and then the pendulum will swing back. We'll have midterm elections in two years, but these are hard to predict.

The nature of what I'm talking about with pragmatism and de Tocqueville is the notion that you need to keep learning loops, you need feedback, and you need to get the information flow. The US is a very tumultuous political and economic system. But at the same time, you've got advances, say, in artificial intelligence, that could transform the world.

GT: You touched upon US' ability to create new, even unexpected, opportunities in the face of difficulties. Do you think there are still opportunities beyond imagination in China-US relations in the future?

Zoellick:I hope so. I am an optimist by nature. Let me give you a small example. I talked about artificial intelligence. I know that many Chinese are excited about the success of DeepSeek. I don't see DeepSeek so much as a Chinese versus US system. I see it as an example that progress in AI is moving very fast. And DeepSeek signals a new phase, in which you can spend less money and focus on a more particular set of issues. We're going to move from investment in enabling systems like models to attention to applications.

When the iPhone was created in 2007, it was a neat device, but it didn't have anywhere near the applications that we now have. DeepSeek is an example of prodding that kind of process of change. We might actually find that the models become more commoditized. The real value is in how you apply these technologies.

China and the US will manage well enough in their own ways, I'm concerned about some of the developing countries and whether they'll be left out of this process. My point is that, as my work with China suggested, China and the US share our world. We have different political systems and different security concerns. But insofar there's some common interest in making that world more successful, that's a plus.

GT: Have your views received any feedback from the current policymakers?

Zoellick:My views are minority, but the nature of my system is that, as the debate continues, maybe sometimes people will come over to my side.、

GT: You raised a question in the book: What should or what could US' mission be?MKsport People's understanding of this question has evolved over time. Given the growingly acknowledged trend of multipolarization, how would you answer this question today?

Zoellick:What I was trying to raise with the notion of US' purpose was that it has changed over time with the circumstances. When the US was a young country, its purpose was simply to survive as a republic in a world of empires. Then, in the middle of the 19th century, we had a civil war, it was about surviving as a country. Then, in World War I, Woodrow Wilson said we need to make the world safe for democracy. He didn't say to make it a democracy, but to make it safe for democracies. In World War II, Franklin Roosevelt talked about the four freedoms. During the Cold War, from the US perspective, it was the leader of the Free World. After the Cold War, it was the indispensable power. It has changed.

The Trump administration talks about "America First" and making America great again. Its perspective is that the international system created over the past 70 or 80 years has cost the US, and it hasn't gotten enough of the benefits. It is trying to renegotiate that, whether with alliances, trade, or other issues.

My view is that there is a way in which you can have a national interest and an international interest. When the world grows, the US benefits. If Mexico becomes more successful, we have fewer problems on our border, and they'll buy more from the US.

Your question is a good one, because in a way, when I put out those missions, I wasn't trying to say this is a rulebook for all time. I'm saying these are topics that keep arising, and in some ways, they give you a good way to examine the current US agenda.