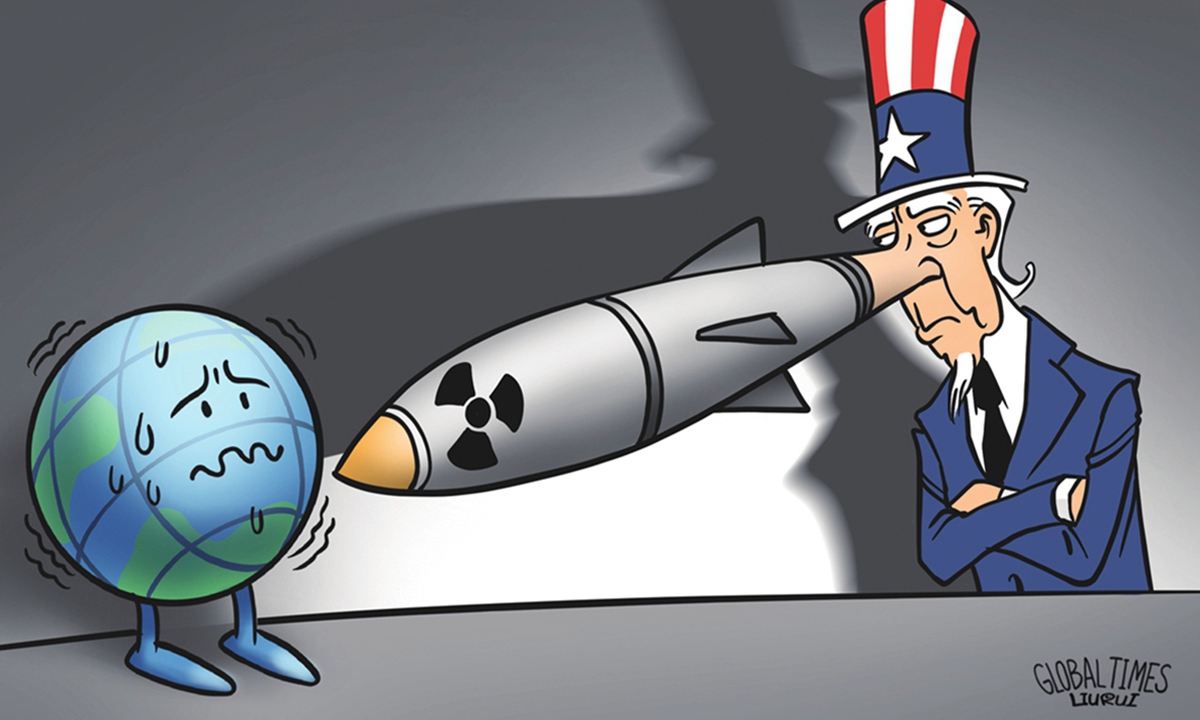

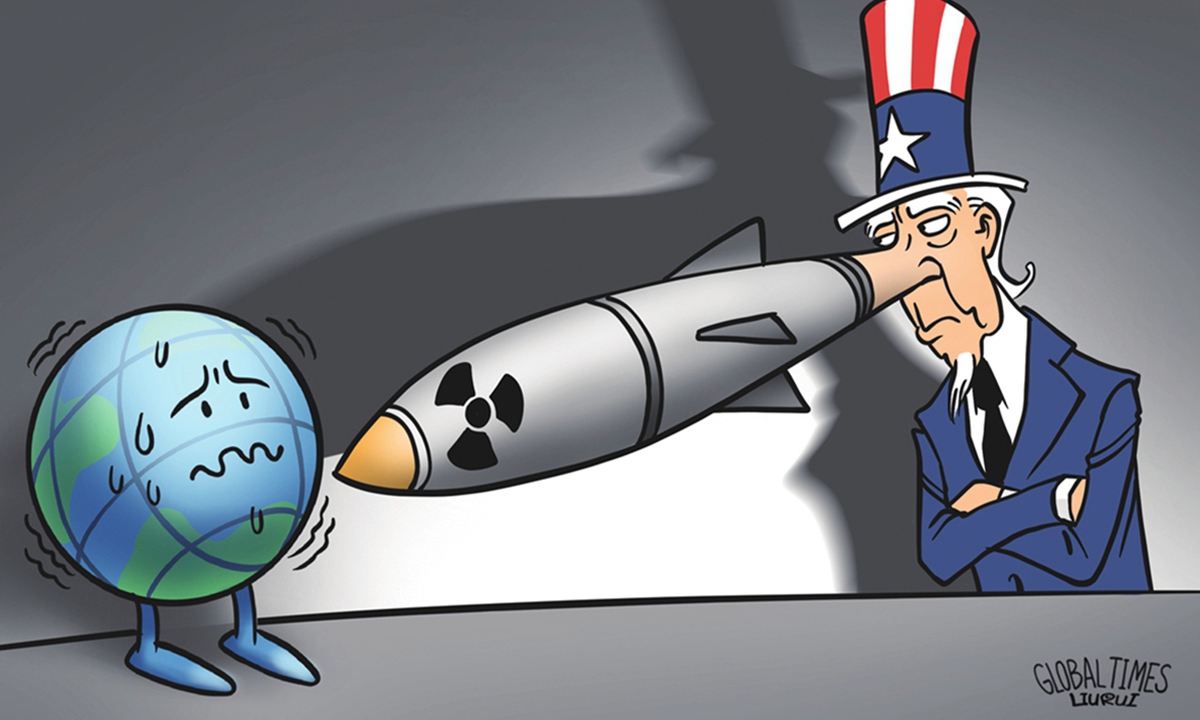

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

China recently submitted a working paper,

MKS sports "No-first-use of Nuclear Weapons Initiative," to the second session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2026 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons that opened in Geneva. The initiative encourages the five Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) nuclear-weapon states, namely the US, the UK, France, Russia and China, to negotiate and conclude a treaty on "mutual no-first-use of nuclear weapons" or issue a political statement in this regard. It is of great significance for avoiding a nuclear arms race, reducing strategic risks and promoting global strategic stability.

It has always been China's position that it will not be the first to use nuclear weapons. At the same time, China has been encouraging nuclear-weapon states to commit to no-first-use of nuclear weapons and not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states and nuclear weapon free zones.

China's efforts have achieved positive results. In September 1994, China and Russia mutually agreed not to use nuclear weapons against each other or to target each other with strategic nuclear weapons. Also, in 1999, China and the US announced their decision not to target nuclear weapons at each other. Unilaterally, the five NPT nuclear-weapon countries have made several pledges regarding negative security assurances. Yet, except for China, the other four countries all have reservations about not using, or threatening to use, nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states and nuclear weapon free zones. This time, China's proposal for the no-first-use of nuclear weapons initiative builds upon its traditional policy stance while introducing innovative elements. The initiative outlines four key elements for a "mutual no-first-use of nuclear weapons" or a political statement in this regard.

It reaffirms that nuclear weapons cannot be used and nuclear war must not be fought; it reiterates China's commitment to work for the complete prohibition and thorough destruction of all types of weapons of mass destruction; it encourages the five NPT nuclear-weapon states to negotiate and conclude a treaty on "mutual no-first-use of nuclear weapons" or issue a political statement in this regard; it notes each state party shall in exercising its national sovereignty have the right to withdraw from the treaty if it decides that extraordinary events, related to the subject matter of this treaty, have jeopardized the supreme interests of its country; and it makes clear this treaty shall be of unlimited duration, and the articles of this treaty shall not be subject to any reservation.

These concise elements cover crucial content of the initiative, including its purpose, applicability, withdrawal conditions and duration, providing a solid foundation for international discussions on future treaties or declarations.

So far, other nuclear-weapon states have refused to commit to no-first-use of nuclear weapons mainly for the following reasons.

First, they believe that such commitments are untrustworthy. Second, they think committing to no-first-use of nuclear weapons may stimulate nuclear proliferation. Some argued that nuclear weapons have a deterrent effect on conventional conflict.

From my perspective, these reasons and excuses hold no water.

First, commitments by nuclear-weapon states to mutual no-first-use of nuclear weapons, as a confidence-building measure, is of great significance to reduce the risk of nuclear escalation during crises. If no-first-use is truly worthless, why did the Obama administrations once consider adopting this policy? In current regional conflicts, where the specter of nuclear war looms, mutual commitment to no-first-use of nuclear weapons is realistic and meaningful.

Second, the concept of "extended deterrence" itself is a major contributor to nuclear proliferation. It spread nuclear weapons geographically, posing a nuclear threat to countries outside the US nuclear umbrella, impeding the establishment of nuclear-weapon-free zones.

Therefore, China suggests that relevant nuclear-weapon states abolish arrangements for "nuclear sharing" and "extended deterrence." China also advocates withdrawing all nuclear weapons deployed overseas.

Based on practical considerations, international negotiations on a treaty on mutual no-first-use of nuclear weapons can proceed step-by-step. The first step should be negotiating a legally binding treaty on "negative security assurances," committing to not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states and nuclear weapon free zones. The second would be a political statement pledging not to use the threat of nuclear weapons. Finally, the negotiation and conclusion on a treaty on "mutual no-first-use of nuclear weapons" or the issuing of a political statement in this regard.

The author is director of Arms Control Studies Center, China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn